Today I had some phenomenal experiences in Israel- only because I speak Arabic. Rather than write a post with facts and figures about why my fellow Israelis should learn the language, I’m going to simply share my story.

This afternoon, I stopped by a sandwich shop. While the chef made me a chicken in pita sandwich, I asked him where in the neighborhood I could buy a notebook. He said he was new to the area so he didn’t know. I told him I was new too. He lives in North Tel Aviv but happens to work at this restaurant a couple days a week, only as of recently.

After explaining I was an oleh chadash, a newly-minted Israeli, he welcomed me and asked where I was from. I then asked him what his family’s origin was. Turns out he’s Moroccan and moved to Israel when he was very young. Not looking more than 35 years old, I was stunned. Most Moroccan Jews in Israel moved during the 1950s. He even grew up speaking Moroccan at home- something rare among young Israelis. We switched to Arabic. I told him how cool it was to talk to a Jew in Arabic. In America, where 90% of Jews are Ashkenazi, it’s almost unthinkable to find a native Arabic speaker in your synagogue. And yet here I was talking with a 35 year old Moroccan Jew in Arabic.

Wrong. Amir (pseudonym) is Moroccan but, to the surprise of probably everyone reading this, is Muslim. And not a convert- a Muslim by birth.

How did we get here? So first off, Amir tells me he grew up in Tira. I’ve heard of Tira before and I did some googling to double check- yes, in fact, it is an Arab town. It’d be quite out of the ordinary to find Moroccan Jews living in the middle of an Arab village here. In addition, while many Moroccans can get by in Levantine Arabic (the dialect I speak along with Arab-Israelis/Palestinians), he had a strong facility with the language and didn’t revert to any Moroccan-isms. I’m familiar with some because several of my college Arabic professors were Moroccan.

So finally I asked him: “Tira is an Arab village- are you Jewish?” I figured maybe, working in the neighborhood we were in, he might be afraid to reveal his identity. He then told me he wasn’t Jewish but was most certainly Moroccan. So then the obvious question- how on earth did he get here? For those of you unfamiliar, Israel and Morocco don’t even have mutual embassies, let alone coordinated immigration policies.

At this point, there’s a Jewish Israeli sitting in the cafe too. Moshe is of Moroccan descent, but barely speaks the language. But of course, even though Amir had told me over and over how great my Arabic was, this other shmo had to tell me I don’t speak like an Arab- which is bullshit because I have a great accent. Like most insecure people, he chose to take his own identity issues out on me (look for a future blog on Mizrachi identity).

Noticing the other patron, Amir turns away from him and leans in to tell me: “It’s a secret, but my family worked with the Israeli government and that’s why we were able to come.”

Wow. First of all, I have absolutely no way to verify it. But in the interest of protecting his privacy, I did use a pseudonym and will not reveal the restaurant. I do have to say though that after having talked for about an hour, he seemed like a legit guy and I don’t have any reason to question what he said.

As I headed out from the restaurant, we gave each other a smile and a hearty “ma3 asalaameh”. Nice to make a new friend!

Still in shock and full of adrenaline, I walked through Tel Aviv until I found myself hungry again. This time, I popped into a Cofix, a cafe here, and no joke, I hear my favorite Egyptian pop song. It’s something that’s literally on my phone right now.

Seeing as how almost no Arabs live in the center of Tel Aviv, I was pleasantly surprised. I went in and addressed the young man in Arabic: “hey, is this your music?” He looked a bit confused. So I switched to Hebrew. And it turns out, yes this is his music.

I switched back to Arabic but found he only understood about half of what I was saying. And not because, like Moshe thought, I “can’t speak like an Arab”. Rather, it’s because he’s not Arab- he’s Jewish!

What?!? Ok so this kid, Nir, his family is Syrian. His parents speak Syrian Arabic at home- the exact dialect I speak. He grew up with it and in his own words “is in love with Arabic”. Which is why he blares the music in his cafe in the middle of Tel Aviv.

I asked him if he understood the song. He said his Arabic isn’t so strong but he wants to learn. I told him I could teach him. He was confused- how does an American Jew become Israeli know Syrian Arabic? And why not just Modern Standard Arabic? I explained that I studied with a Syrian professor from Damascus in college- in the United States. He thought I was kidding but then I started speaking to him in Syrian again and he realized I was the real deal. He took my number- I hope he calls and I can connect him to his heritage. You could digest that sentence for a lifetime.

Before I left I asked the second barista if he understood the song. He could pass for Arab, but it turns out he was Jewish. He said he thought it was about peace. What a beautiful sentiment. In a day and age when many Israelis and Americans would assume the worst of a song in Arabic, this young kid, smack in the middle of Tel Aviv, assumes it’s about peace. It just touched my heart.

I told the kids the song was actually about encouraging people to vote in the Egyptian elections. I explained some of the verses and they were eager to learn.

So here we were- three Jews, one Ashkenazi American, one Syrian, and one from who knows where. Sitting in Israel, listening to Egyptian music, babbling in a mixture of Hebrew and Arabic.

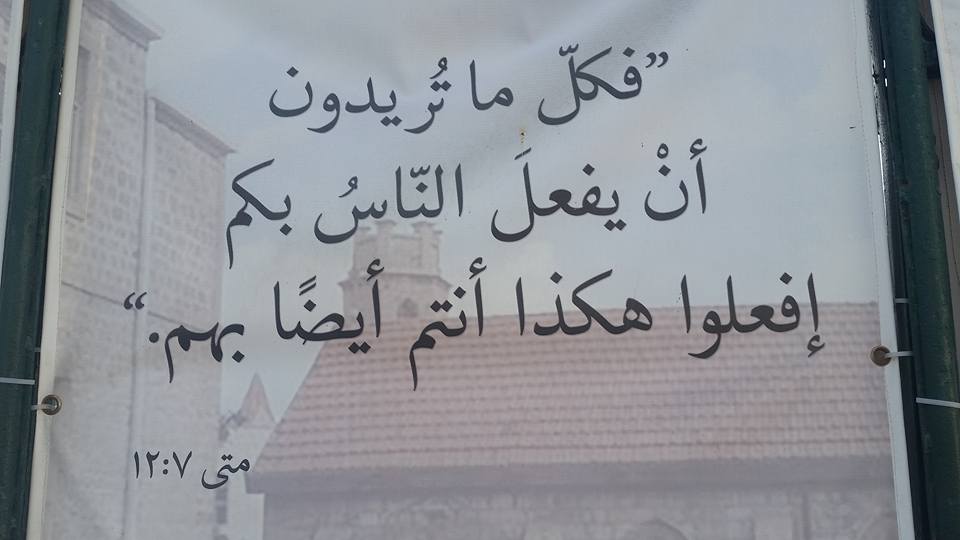

If there’s one thing I can take from today it’s that where Jewish starts and Arab ends isn’t so clear. Just like the bilingual script in my cover photo. When coming to Israel, the absolute best thing you can do is to leave your assumptions at the door. And the second best thing you can do is to learn a language so filled with love and art and history that you’ll be bursting at the seems making new friends from every race and religion. And that language, my friends, is Arabic.

You must be logged in to post a comment.