When it comes to economics, I believe the more equal we can make our society, the better. Ideally, that’d mean less state and corporate control and more resources in the hands of the people. And as we work towards that goal, I believe in a strong safety net- universal healthcare, guaranteed housing, access to healthful food, free public transportation, and more.

What I’ve come to realize, particularly due to my stay in Israel, is that economic justice is not enough.

What does that mean? What I mean is economic justice is crucial- it helps people survive. If you look at Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, economic justice provides people with the foundation in order to reach higher goals in life. It provides for your physiological needs (air, water, food, shelter) and safety needs (financial security, health, safety).

If you look at the pyramid below, you’ll notice that more emotional needs, like love and esteem are built upon the foundation of the needs addressed by economic justice:

In other words, you need economic justice to give people the opportunity to build their self confidence, to be able to focus on their love life, and to realize their dreams.

And yet, what’s also clear is that economic justice alone will not help someone achieve these higher needs in life. Having a good salary certainly can make me feel happy and secure, but it won’t in and of itself make me feel loved.

Which is where we come to culture. First, let’s define culture. Culture, as I see it, is art, music, language, food, religion, customs, clothing, and so much more. In short, it is a series of practices that gives life meaning. It helps us feel rooted. It doesn’t mean that culture stays stagnant- it always changes. Yet if we don’t have some reference point for how we interact with the world, our self-esteem suffers and we can feel devalued. Especially when the surrounding society demands we abandon our culture.

Incidentally, when I did a Google search on the psychological benefits of culture, an Israeli researcher appeared. Dr. Carmit Tadmor studies the role of multiculturalism as it relates to conflicts in Israeli society. Both she and the American Dr. Francois Grosjean, whose article helped me find her, argue that biculturalism is a benefit. That people with more than one culture tend to be more creative, more flexible, more able to wrestle with ambiguity, and more professionally successful. And quite important for Israel- they are more willing to acknowledge different perspectives and consider their merit.

Considering all the benefits of culture, one can imagine the great harm involved in destroying it. If access to your culture (and the ability to add new ones) gives people confidence and creativity, stripping people of their culture causes psychological harm. When a Yemenite child is forced by his Kibbutz to cut off his peyos, his sidelocks, one does not need a great deal of imagination to fathom the psychological harm. Or, in the case of America, when newspapers advertised jobs saying “No Irish Need Apply“.

This last example is particularly illustrative. Professor Richard J. Jensen at University of Illinois-Chicago published a book entitled “No Irish Need Apply: A Myth of Victimization”. He claims discrimination against Irish-Americans was exaggerated. I’m pretty much always suspicious of someone who uses the phrase “myth of victimization” because it’s used to tell people their pain isn’t real. To invalidate them. Perhaps to invalidate themselves.

This attitude, unfortunately, is quite common in the U.S. I once met a man of Irish ancestry- actually proud of his ancestry but not engaging with directly. That is to say, he read books, he visited the country, but on a day-to-day basis, the food was cheese dip, the language was English, the music was Sweet Home Alabama- and that’s about it. When I once asked him about his prejudices towards immigrants- why Latinos, for instance, couldn’t continue to speak Spanish- his answer was telling.

“When my grandparents came to America, they spoke Irish Gaelic. But they never taught it to us because they were in America. And here we speak English. And I’m glad they never taught it to us because that’s not what you’re supposed to do here.”

In other words, he justifies his current prejudice towards immigrants who strive to maintain their culture by citing his own family’s pain- and even justifying that pain. Invalidating the suffering his family endured. That continues to leave his family rather rootless today. And voting for politicians to expel his immigrant neighbors who suffer the same fate his family did.

Which brings us back to Prof. Jensen’s book. As an American Jew and a Washingtonian, what I discovered made me so proud. A 14 year old girl, Rebecca Fried, a student at D.C.’s Sidwell Friends School, wrote a thesis disproving Prof. Jensen’s claims. It started with a simple Google search and she found tons of examples of discrimination, including racist job postings. Prof. Jensen’s work was a sham- as other professors then began to discover he had an anti-Irish and anti-Catholic ideology. It’s also sad because his last name is Scandinavian- he clearly has immigrant roots himself that maybe his own family was torn away from. That he continues to inflict on others.

What makes me particularly proud about this? First off, she’s a fellow Washingtonian. We come from one of the most diverse metropolitan areas in the world and it definitely helped me become the multicultural person I am today. It’s basically impossible for you to live in the D.C. area and not interact with people of different backgrounds and like Dr. Tadmor’s research indicates, this changes your mentality for the better.

Secondly, I’m going to make an assumption – hopefully correct – that Rebecca Fried, daughter of lawyer Michael Fried – is probably Jewish or at least of Jewish ancestry. The name is so so American Jewish that I’d be surprised if she wasn’t somehow connected to our tradition. Although America always finds ways to surprise you 🙂

Working off this assumption, a 14 year old girl of Jewish ancestry helped Irish Americans reclaim their cultural identity. And unravel a hateful argument against them.

Why does this not surprise me? Because American Jews- perhaps all Jews outside Israel- understand what it means to be a minority. And- most importantly- if we continue to identify as Jewish in any way we are in fact maintaining our culture. All American Jews are bicultural. And therefore we enjoy the benefits of this identity- and understand the challenges. While we faced (and continue to face) pressure to assimilate in the U.S., our resilience helps explain why American Jews “earn like Episcopalians and vote like Puerto Ricans.” Which is to say that because we’ve maintained our culture, even though our economics should push us to vote Republican, we voted 71% Democrat in 2016.

Not to say people of different parties can’t be empathetic to immigrants, but in the current climate I think it’s fair to say Democrats are more open to multiculturalism.

I believe our biculturality helps explain why American Jews tend to be more empathetic to refugees and more open to diversity when compared with their Sabra counterparts in Israel.

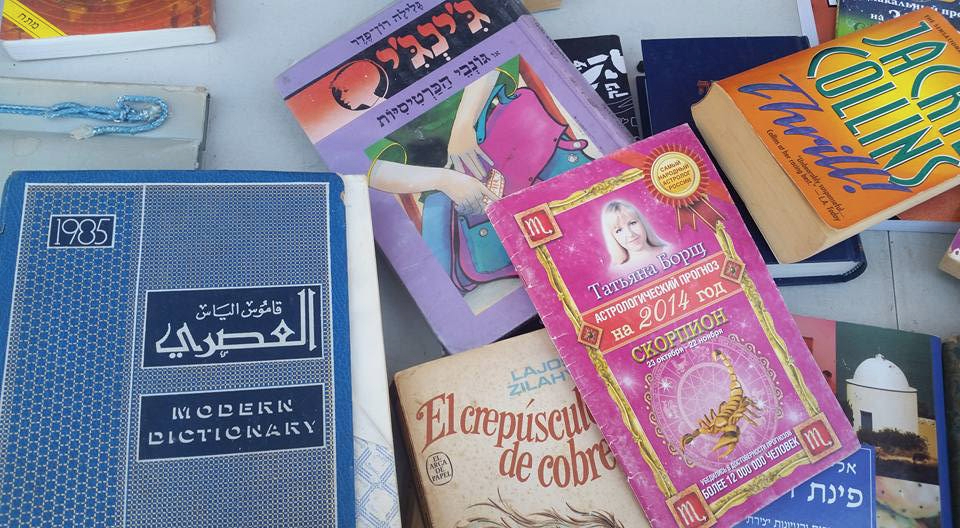

When Jews came to Israel, they had their cultures ripped from their bosom by the Sabras who already lived here. Yiddish, Judeo-Iraqi, Ladino- thousands of years of Jewish history were thrown out the window. Kids were shamed for speaking Jewish languages! Within just a few generations, many of these languages had become extinct or endangered. Not because of anti-Semitism in another country, but rather because of other Jews who denied them the right to maintain their culture. Because of bullies deeply insecure about their own cultural identity.

So how does this relate to social justice? First off, we started by talking about economic justice. The Israeli state- especially in its early years- did actually have quite a focus on economic justice. The social safety net that developed far outpaced anything we have in America. The government was pretty socialist- this is the origin of the Kibbutz- a commune. There was (and is) a communist party in Israel- in the Knesset.

And yet there was a blind spot. Racism. Culture. The government may have thought that if it simply erased Diaspora Judaism- the “icky” Moroccan superstitions, the “grating” noise of Yiddish- that it could entice people with money. With jobs, with education, with healthcare. To switch their identities. Not to have both- for example- Moroccan and Israeli identities. But rather “Israel #1 only amazing awesome nothing better”- that’s it.

Well guess what? That has never worked in history. Because what happens when you strip someone of their identity? Let’s say they have their physiological and safety needs taken care of (not always the case here, but roll with me)- what’s missing?

What’s missing is culture. Something to root you, to comfort you, to enrich your life. Because Sabra culture is not a culture- by design. Sabras when creating the State of Israel wanted to be the “anti-culture”. That by negating their roots, they were making something new. True- but the issue is you can’t create something out of nothing. Your mentality, your traditions, no matter how much you hate them, impact the way you see the world. And simply by telling yourself that that’s not OK turns you into a monster. Into someone who hates both herself and- in particular- her neighbors who continue to hold on to the traditions she despises.

I think this explains why in Israel, and in the U.S., the people who tend to be most anti-minority and anti-diversity are the people who had their culture stripped from them. Who continue to operate in a vacuum of Palestinian falafel they call Israeli and pizza they call American.

The reason Jews have been- and in some cases continue to be- hated in the Diaspora is because of our tenacity. Our desire to hold on to our evolving traditions even when they’re not the norm. To celebrate our holidays, to embrace our sense of humor, to learn about our history, to wear a yarmulke, to want to pass these traditions down to the next generation.

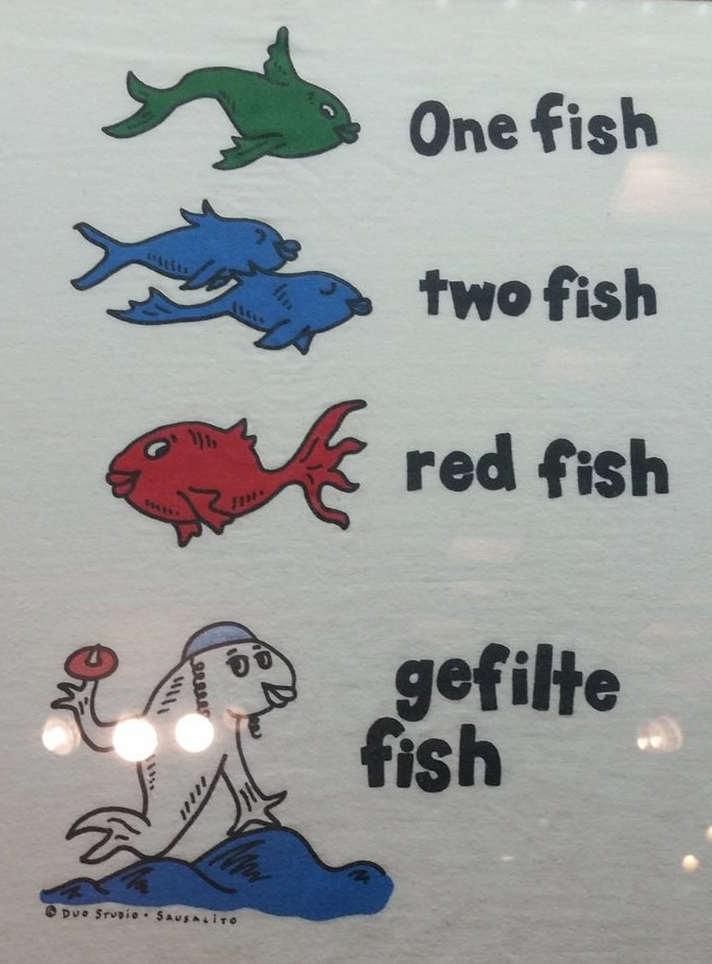

Our willingness to remain different while enjoying the best society has to offer, our biculturality, is what makes us queer. It’s what makes us more complex than economic justice. Because you can give me bread, but I want roses too. I want a sense of identity. And so do Mizrachi Jews and Sudanese refugees and Latinos and Black Americans and religious Jews and Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazim. As do many people alienated from their cultures- take this opportunity to learn!

In short, the right to a cultural identity not only makes you a happier person, it makes you more empathetic to others, it makes society more progressive, and it makes for less bitter people for the state to rally to hate others.

This new secular year, let’s make it our mission to realize that economic justice is crucial and not enough. Our cultural identity changes the way we see the world and when we have the right to exercise it, it can help us be better people and make our society one worth living in.

May it be so.

You must be logged in to post a comment.