One might be surprised to hear this, but Yiddish lives in Israel- and not just among Hasidim. Yiddish is the traditional language of Ashkenazi Jews like me. Before someone says something stupid, let me clarify something- Yiddish is NOT a “mixture of German and Hebrew”. It is also not only a Hasidic language- it has existed for at least a thousand years as a distinct language, whereas Hasidism has been around for about 400. On the eve of the Holocaust, 13 million Jews- socialists, communists, Zionists, anti-Zionists, Hasidim, secularists- spoke the language.

Yiddish is an archaeology of the Jewish people and linguistic proof of our ties to the Land of Israel. About 2000 years ago, Romans expelled Jews from Israel and destroyed the Temple in Jerusalem. The Jews who weren’t executed were expelled or enslaved. Many eventually made their way to other parts of the Roman Empire, where their Aramaic and Hebrew vocabulary became enriched with Latin words. For instance, a famous Yiddish word (still said today even in Jewish American English) is “bentsch”. To bentsch is to say the special prayer after eating a meal, coming from the Yiddish word “bentschn”. This word comes from the Latin root “benedicere” meaning “to bless” like “bendecir” in Spanish.

As was the custom of European Christians for the 2,000 years of Jewish existence on their continent, time after time Jews were expelled as we were scapegoated for various social problems. Other minorities today can probably relate. And so with each expulsion and migration, Yiddish was enriched with new vocabulary- Italian, French, and eventually Germanic languages. To be clear- at the time Jews started settling in present-day German speaking areas like Switzerland, Germany, and Austria, there was no such thing as the German language. There were a variety of Germanic dialects (some of which are still spoken), but no unified language.

Yiddish borrowed heavily from their neighbors’ lexicon, although in some cases developing new meanings particular to their community. For instance, while in German “shul” means “school”, in Yiddish, it can mean “synagogue”. Hebrew and Aramaic also interplayed with the Germanic words. For instance, “froynd” in Yiddish is a “casual friend” or “acquaintance”, similar to the Modern German meaning. But in Yiddish, there is another level of friendship- a “chaver” (or “chaverteh” for a woman- that’s a Hebrew word with an Aramaic suffix). That’s a real close friend. And it says something about the value still placed on Hebrew (known often as “loshn koydesh- holy tongue”) even in the Diaspora.

As German-speaking peoples decided to butcher Jews during the Crusades and expel them from their cities, Jews went eastward. Believe it or not, initially Polish and Lithuanian rulers (these countries today are more well known among Jews as places we were massacred) welcomed Jews. Jews became merchants and built communities in Poland- and then all across Eastern Europe, down to Romania and Ukraine. Name a country in Eastern Europe and we made our way there.

Of course the Slavic vocabulary lent a new angle to the language. While the Jews that remained in Germany, Holland, and France continued speaking Yiddish- a new dialect developed: Eastern Yiddish. Bubbe, Zayde, Tate, Mame- grandma, grandpa, mom, and dad- are all derived from Slavic roots. The first two are to this day used by many American Jews to talk to their grandparents.

Meanwhile, Hebrew and Aramaic maintained a strong presence- perhaps also due to the fact that these languages were used extensively in prayer and in study. They maintained such a strong presence that when Zionists aimed to revive Hebrew as the main spoken language of Jews, they looked to Yiddish for both Hebraic words and for Yiddish expressions to translate. The modern Hebrew words B’seder, mamash, b’tachlis, chutzpah, and so many more are of Yiddish origin. Which is to say- they are Hebrew (“holy tongue”) words that made their way into specific usages in Yiddish- and these usages were copied into Modern Hebrew in a way they didn’t necessarily exist in the Torah or other Jewish languages.

Speaking of translated phrases, did you know the Hebrew greeting “mah nishma?” is literally a translation of the Yiddish phrase “vos hert zach?”, meaning “what is heard?” Even the famous “mah pitom?” is a translation (calque) from Yiddish. If you speak Modern Hebrew, you speak more Yiddish than you thought!

Which brings us back to the language. After the Nazi Germans and their anti-Semitic collaborators murdered 6 million Jews, most of them Yiddish speaking, the language was devastated. Ashkenazi Eastern European civilization was brutally brought to an end after 2,000 years of life on the continent. The language itself was feared extinct as the only remaining centers- the U.S. and Israel- were encouraging linguistic assimilation into English and Hebrew respectively.

In particular, in Israel, the government actually forbade non-Hebrew newspapers and theater performances. Feeling Yiddish (and languages such as Ladino and Judeo-Arabic) was a threat, there was an actual “brigade” of volunteers who would go around shutting down Yiddish events. I can’t think of something more horrifying to experience than for a Holocaust survivor to have a fellow Jew attack them for speaking the mamaloshn- their mother tongue.

Over the years, the remnants of Yiddish faded both in America and in Israel as Jews were told (either by Christians in America or fellow Jews in Israel) that their language was “lame”, “ignorant”, “backwards”, and (in Israel) “Diasporic”. For all of Israel’s renewed interest in multilingualism and greater tolerance for diversity, I experienced this attitude myself when I posted my English blog in an LGBT Israeli group (with a description in Hebrew) and someone berated me saying I needed to write my blog in “the holy tongue”.

In particular, people have called Yiddish a “dialect” or “jargon” over the years. This goes back hundreds of years in Europe- it was a deliberate effort by ruling Christians to demean Jews by insulting their language. And sadly, some Jews internalize(d) this thought even though Yiddish published its first dictionary before German and tens of thousands of books, 12,000 of which are preserved digitally here. Yiddish is a language with many influences, just like English. It is a storied and beautiful language. As a famous Yiddish linguist Max Weinreich said: “a language is a dialect with an army and a navy”.

When my ancestors moved to America in the late 1800s and early 1900s to escape anti-Semitic violence in Eastern Europe, they spoke Yiddish (one of them also spoke Romanian!). I even found the Census records to prove it. With each subsequent generation, a bit more of the language was lost, but it is still present today in my dialect of English, where words like “schlep”, “shlemiel”, “shmear”, and “oy gevalt” are omnipresent. And sometimes need to be explained to non-Jews!

Yiddish has always acted as a storage device for Jewish culture. There are certain things that just can’t be expressed in other languages. And while Germans can understand much of it- there’s a lot they can’t. And Jews can change their register (by adding more Hebrew and Aramaic, e.g.) to make it harder for them to understand- which is the point. It was a clever way for Jews to understand their neighbors but speak more secretively if needed to protect the community.

Yiddish, as we saw, also stored a lot of Hebrew. In some ways it kept the language alive over the course of 2,000 years. I dare anyone who says Jews aren’t tied to this land to explain to me why Lithuanian Jews were speaking a language 20% made of Hebrew words.

In the end, Yiddish shows that Judaism is not just a religion, it is also a culture- a people. It’s not coincidental that a few hundred years ago, a Jew in Poland could communicate better with a Dutch Jew than with a non-Jewish Pole. Jews’ primary relationship was with other Jews. There is no such thing as Presbyterian cuisine, literature, and language- because that’s a religion. The word religion is a foreign concept to Judaism- we are a tribe. You cannot fully separate the culture and the spiritual nature of our people- although many a secularist (and Haredi) have tried. They are inextricably tied together just like natives living in the Amazon. Where one starts and one ends is unclear- and there’s no need to clarify it.

Growing up speaking Jewish American English, I was always exposed to Yiddish. All of my grandparents spoke it or understood it to varying degrees. And it peppered my conversations. It’s a very expressive and fun language with a soft side to it. Despite some of the efforts of Hebrew purists to rid the language of Yiddish, I actually see a lot of it reflected in Israeli culture and language. It feels comfortable.

A few years ago, I found a private tutor to start learning the language in earnest. I then was blessed with the opportunity to go to the Workmen’s Circle “Yiddishland” program in New York. There I learned not only the language, but also the culture- the music, the traditional dancing, so much.

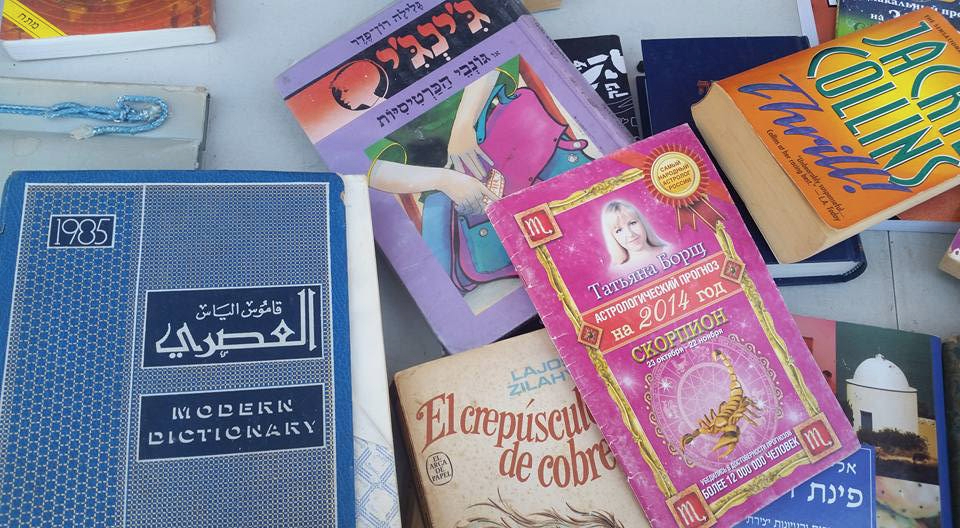

When I made aliyah and moved to Israel, I wasn’t sure how much yiddishkayt- Yiddishness- I would find. I’ve been pleasantly surprised at how vigorously Hasidic communities here are preserving the language- my cover photo is a bunch of newly printed Yiddish books for children in Bnei Brak. With Hasidic Jews’ high birthrate, the language is about to make the comeback of a lifetime. At the same time, I personally wanted to find a more progressive setting for my Yiddish too.

I’ve been pleased to connected with organizations in Tel Aviv like Yung Yidish (a library and concert venue in the Central Bus Station), Arbeiter Ring, Yiddishpiel Theater, and so much more. I even got the chance to see a Yiddish musical based on the Barry Sisters last night! The subtitles (which I was proud that I only needed occasionally) were in Hebrew and Russian. Not a small number of Russians here also speak the mamaloshn- tribute to how international and cosmopolitan this language is.

To conclude, I’d like to share a story about how Yiddish lebt- how Yiddish lives. I went to the library here to try to find Yiddish books. I was disappointed when the librarian said their branch had none. Feeling despondent about the future of the language, I asked what other languages they had. She mentioned French, which I also speak.

I headed back to the French section only to find something curious. A French book- almost a hundred years old- by famed Yiddish writer Sholem Asch! In other words, a Yiddish book…translated into French! I shared my excitement with the librarian, who was astonished. I may very well have been the only person to discover this.

This is how Hebrew survived in Yiddish- and how Yiddish now survives in Israel. Little fragments of a prior world integrated into a new form. An immaculate metaphor for Judaism itself. And I’m telling you- don’t count Yiddish out. Because those sparks of Yiddishkayt are being rekindled- in Bnei Brak, in Mea Shearim, and right here in the most secular place of all- my home, Tel Aviv.

You must be logged in to post a comment.