Lately I’ve been writing some pretty critical posts about Israel. I think they are necessary and true.

It’s been making me reflect on what I still like about Israel. To be honest, I like a lot less about Israel than I did when I first came here. The racism, aggression, sectarian hatred, and ignorance make my daily life here quite hard. And hard for pretty much everyone here. Not everyone embodies these problems and a lot of people do- more than I expected. In every religious, political, and ethnic group here. It’s sad to see the Holy Land so filled with hate.

So it got me thinking- what do I like about Israel?

I like the healthcare system. Israeli healthcare is light years ahead of America, something I noticed when first arriving here. Treatment is almost always cheaper and more often than not, free. Even for going to specialists like allergists, sleep labs, and psychiatrists who are part of your kupah, or health network. Dental work costs a miniscule amount of what it does in the States and there are no deductibles. You don’t have to guess whether you’ll be covered. All your records are digitized and you can make appointments on an app. The system has varying degrees of access in Hebrew, Arabic, Russian, English, and French.

I like that you can talk to random people here and it’s not “weird”. At least in Washington, D.C., where I lived before making aliyah, when I tried to help someone or make small talk, I often felt like I was imposing. Or that the other person wanted to know what I wanted out of them. As if a conversation itself wasn’t sufficient- there must be some other motive. Here, you can talk with almost anyone, Jewish or Arab, sometimes for hours without having met before. Things are a lot less formal.

The produce is absolutely fantastic and cheap. And unlike in Washington, D.C., you don’t need to go to an expensive farmers’ market to get delicious vegetables. In D.C., the veggies at the grocery store are kind of watery- most of them probably sent from warmer climes like California. According to my friends in Cali the produce is great there. But if you live in D.C., by the time they get to you, they don’t taste so great. Unless you’re willing to shell out money to go to Whole Foods. The market and shops near my house in Tel Aviv have affordable delicious produce all year round. It keeps you feeling healthful and biting into one of those yummy carrots just makes me happier.

If you need help here, you just ask for it. There’s no shame in asking for help and people- both Jewish and Arab- more often than not are willing to help. I’ve been given a free room to stay in a number of times- sometimes by people I had just met- or never met. In the U.S., I of course have crashed with friends but it felt like a much bigger “ask” than here. I once saw a woman on the bus from Jerusalem to Tel Aviv offer to host someone who was worried she wouldn’t be able to catch the train home to Haifa. They had just met 20 minutes beforehand.

There are also a series of things I both like and dislike depending on how they’re used. For instance, I’m less worried about offending someone here when I say something that doesn’t come out right or they disagree with. At times, I don’t feel like I have to “walk on eggshells”, which can be a relief- we all say things that we regret. The downside is that I find Israelis much less empathetic than Americans. So when you are actually offended, people more often than not tell you to stop being upset, rather than acknowledging your pain.

The same goes for rules and formality. In Israel, I have never worn a dress shirt, tie, or suit. Thank God- other than an occasional celebration, I hate these clothes! Here jeans and a t-shirt are totally fine most of the time, even in synagogue. Israelis generally don’t like rules- this is a place where you ask for forgiveness rather than permission. That can be helpful in working out creative solutions for business, plans, or even activism. D.C. often felt rigid to me and stifled my creativity at times. The flip side is that Israelis’ lack of rules often results in less protections. Renters here are regularly scammed by landlords- much more than anything I saw in the States. I’ve been taken advantage of many times here- and it’s even a societal value. Rather than be the “freier” or “sucker”, Israelis often prefer to strike first and take advantage of you before you them. It’s a vicious cycle that explains a lot of the problems here. Israelis often struggle when I say the word “no”. Rules often have a purpose- boundaries need to be respected to treat each other with dignity. So the informality and lack of rules that I like can also a problem.

The cultural diversity is amazing here and threatened. I’ve met Jews from places I never expected- India, Norway, Switzerland, Morocco, Tunisia, Turkey, Ethiopia- and so many other places. With unique languages, traditions, and cuisine. And non-Jews such as Druze (whose heart shaped falafel is in my cover photo), Arab Catholics, Arab Greek Orthodox, Arab Greek Catholics, Maronites, Alawites, Muslims, Armenian Orthodox, Armenian Catholics, and Circassians. Darfuris, Ertireans, Sudanese, Nepalis, and Chinese. I speak all eight of my languages here- regularly. This beauty that I love is what the government threatens by shaming Jews for speaking other languages, by discriminating against Arabs, and by expelling refugees. It pains to me to see such a beautiful gift under attack.

In short, it’s complicated. There are good things in Israel. The nature is also gorgeous, the weather is better than anywhere in the Northeast U.S. or most of Europe. The location is ideal for traveling the world.

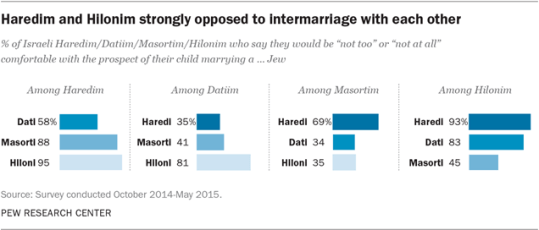

Once the Israeli people do the hard work of pulling themselves away from the toxic ideologies that gave birth to their country, they might find themselves feeling freer. Freer for a secular Jew to be friends with a Hasidic Jew. For an Orthodox Jew to acknowledge Palestinian Arab history. For a Mizrachi Jew to dance to Eritrean refugees’ music. For a secular Ashkenazi to raise his kids in Yiddish. Or an Iraqi Jew to do so in Judeo-Arabic. For a Haredi Jew to see the good in Reform Judaism. For a Palestinian refugee in Lebanon to return home to my neighborhood and for me to help renovate her mosque. For a Christian to marry a Jew. For a Jew to convert to Islam. In short, to be the complex beautiful human beings hiding beneath the divisiveness.

For Hasidic Jews, tikkun olam or “repairing the world” begins within. I couldn’t agree more. To make the world a better place, we must start with ourselves. So see the good things I wrote? Grow them. And where we find barriers in our souls towards our fellow human beings, join me in tearing them down. Inside and radiating out towards the heavens.

Israelis often like to think of themselves as a “light unto the nations”. The thing is to see a candle best, you must first turn off the lights. Scary and necessary. Flip the switch. It’s time for a reset. Let the flame illuminate our path.

You must be logged in to post a comment.