There has always been a yawning communication gap between Israelis and Americans- and between Israelis and the world. Every country and culture has a unique communication style, and in my case, this often leads to challenging interactions with Sabras. Sabras are Jews who were born and raised in Israel, whereas I’m an oleh- I chose to live here.

The sabra communication style most well known is “dugri”. Dugri, from an Arabic word (itself of Turkish origin), means “straight talk”. The word in Arabic means “straight” (like when giving directions), “fair” (like an arbiter not choosing sides), or “honest” (truthful words). In Hebrew, the word means “direct”- but not in the sense of “honest” in Arabic (which is focused on presenting correct objective facts), but rather directly expressing your subjective emotions and opinions, regardless of how they are perceived.

In Israel, this means less pleasantries, less consideration, less politeness, more tough love, more controversial statements, and more blunt judgments.

There are ideological roots to this communication style that have been well-researched. I highly encourage reading Professor Tamar Katriel’s study, which I’m still working through. Going back to the early Zionist pioneer days, ideological olim wanted to rid themselves of what they perceived as a “Diaspora mentality” of formality, nuance, and passivity. Again- this is their perception, not necessarily the facts. The answer, especially for their sabra children, was to be found in a new, astoundingly direct and informal communication style, itself ironically rooted in German enlightenment philosophy. I can empathize that building a new national identity was hard and I also think their attitude towards the Diaspora was pretty hateful.

This style, before I deconstruct the hell out of it, has its advantages. For instance, I’m a very informal person so I like that dugriyut- or speaking dugri- allows me to speculate, to dream, to ponder. I don’t have to cross my i’s and dot my t’s- I can just roll with it. It fosters creativity in me. I also like that I don’t have to think through every word I say for fear of literally losing friendships. Here, an occasional offensive comment is not going to lose you anything. When used properly, speaking dugri can reduce some of the feeling of “walking on broken glass” we face in America when communicating. Also, hearing people’s deep-seated personal prejudices, while valued in Israeli society, for me actually serves as a defense mechanism so I can avoid someone who is actually toxic. I rarely have to guess what people here think.

Now the flip side. First things first- I’m a proud Israeli and I’m an American. My family has lived in the Diaspora for 2,000 years and while I’m glad to be back, I’m not ready to give up the wisdom gained over centuries. I’m a firm believer that it is not only possible, it is desirable to have more than one culture. This is an issue Israel has struggled with from the beginning– as do many countries. I understand- and will continue to learn about- dugri communication but that doesn’t mean I’m going to “negate” my other cultures.

In Hebrew, the ministry that deals with olim is called the “Ministry of Absorption”. I can’t even imagine a more Orwellian phrase, but let’s work with it. Yes, to a degree, I came to be absorbed into Israeli society. But a funny thing happens when your body absorbs something- it changes your composition. And so much in the same way, I intend not just to be changed, but to change this place.

So what does this mean for dugri talk? First off, we need to see some of the negative aspects this style can present. For example, when sabras interact with foreign cultures, including Americans, they often struggle to perceive cultural differences. Just this week alone, on three separate occasions, Jews here made (what I consider) offensive remarks to me about Americans being “fake” etc. This is a common sabra complaint- Americans are polite, but insincere when they compliment you. All the while, I’m sitting there talking with them as an American with ten times better Hebrew than their rrrrresh infected mouths can mumble in my language.

This is endemic of the problem. Because Israelis are sparse- but quite genuine- with their compliments (as befits dugri talk), anything other than that is seen as insincere. What they don’t realize is that it’s simply a cultural difference. When Israelis move abroad and don’t know how to say “please” or “thank you”- or try to say something unacceptably blunt- they lose friends and often struggle to make non-Israeli friends. This is well-documented by a study done among Israeli migrants to Canada. Boy if they think Americans are polite, wait till they meet Canadians haha.

The truth is there are fake people and genuine people in every society. For me, for instance, I encounter some Israeli communication as incredibly insincere- even though it’s just likely just a cultural difference. For instance, especially in Tel Aviv, when people promote upcoming events (or compliment someone for leading an event), a whole litany of “mehamems” and “madhims” and “nehedars” and “merageshs” come out. Basically, just a list of how everything is the most amazing awesome best coolest most wonderful thing ever. It’s enough to make me, as an American, nauseous because it sounds like they’re lying. But what I’ve come to realize is that there’s probably a cultural component to it. Rather than calling all sabras fake, I chose to read hours of academic articles and confront the issue meaningfully.

For me, besides the nuisance of Israelis telling me my country (and implicitly perhaps me and my friends there too?) is fake, I have to wonder if there’s a broader cultural problem at work.

Israelis, unlike almost any civilized society I’ve lived in or visited, have completely separate school systems based not only on race/religion, but also what type of religiosity. There are Arab schools, secular Jewish schools, Modern Orthodox schools, and Haredi schools. These schools operate completely separately in state-sanctioned (and largely publicly supported) segregation. There are social reasons for this- I’m not pretending it came out of nowhere. But the end result is that Israelis rarely if ever interact meaningfully with people from drastically different backgrounds. And they don’t learn how to understand intercultural communication. Nor the value that sometimes, just because you think a thought doesn’t mean it’s best to say it out loud.

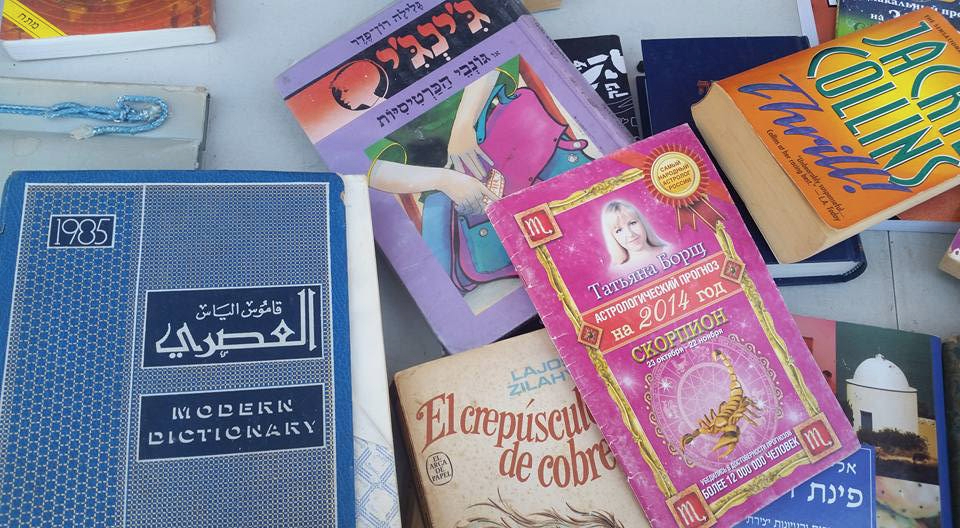

In 6 months in Israel, I have become a regular in Bnei Brak speaking Yiddish, I have visited half a dozen Arab villages in Arabic, I hung out with Samaritans, I watched Karaites pray, I talked with Armenians (in Arabic!), I blasted Eritrean music with refugees at a juice bar, I tutored a Darfur survivor in English. And on and on and on. I know this country much, much better than most of the sabras who’ve lived here their whole lives. And it’s not because they’re bad people. I have learned much from my sabra friends. And they have much to learn from me about their own country. This is one of the most diverse and exciting places on the planet. A place I enjoy even more because of my diverse American upbringing.

Now it’s time for me to dish out some dugri talk (see I do like it sometimes!). Sabras- you’re mostly racist or at best, unappreciative of the diversity that surrounds you. Your difficulty in communicating across the cultures in your own country reinforces your prejudices- including towards olim. I’ve lived all over the world, including spending lots of time in the Deep South in the U.S., and this is by far- by far- the most openly hateful society I’ve lived in. Not just in terms of race, but also in terms of prejudice between different sectors of society (Secular vs. Orthodox, Ashkenazi vs. Mizrachi, etc.). There are some of the most incredibly kind and hospitable people here too. It’s just that the level of judgmental speech and behavior is mind boggling and frankly makes me appreciate my American upbringing- and question whether I want to raise my kids here.

In particular, there are times when the secular Ashkenazi liberal elite here sounds like a bunch of American tea partiers who long for the 1950s. An era in which the government was basically run by a bunch of white men (them), when Holocaust survivors were told they went like “sheep to the slaughter”, when Arabs were under military rule, and Mizrachi Jews lived in impoverished camps. But at least in the “good old days”, the government was more secular i.e. more like them. Perhaps not coincidentally it is this same demographic that coined “dugri talk” generations ago. Language is power.

The key is that every culture has its communication style. It was hard for me to write a blog that was in English but appropriately non-judgmental for an American and appropriately dugri for an Israeli. And I’m still learning about Israel even though I speak the language fluently. I will always be learning. I recommend all olim- indeed all tourists- learn about Israeli dugri talk. And sabras- if you care at all about the millions of people living here born in other countries (or your own ability to travel abroad without offending people)- learn about yourselves. You don’t have to give up your directness but you do need to learn how other cultures work. Because it’s not that all Americans are fake. It’s that you’re not self-aware.

Do your homework. That’s my dugri talk for the day 🙂

p.s.- my cover photo is a paper I used to teach a Swahili-speaking Tanzanian in Holon about Hebrew vowels…via Arabic because she’s an Arabic teacher. Intercultural communication isn’t a hobby- it’s a lifestyle. Open your eyes and join the miracle 🙂

You must be logged in to post a comment.