Two weeks ago, I approached my friends at FluenTLV about starting a Yiddish table. FluenTLV is a fabulous event (my favorite in Tel Aviv) where people get together to exchange languages. I offered to represent the language and they were thrilled.

Last week, the first week we did Yiddish, probably 3 or 4 people came and it went well. One German guy, a couple Jewish Americans, and an Israeli. Given how stigmatized my heritage language is in Israel, I was pretty happy.

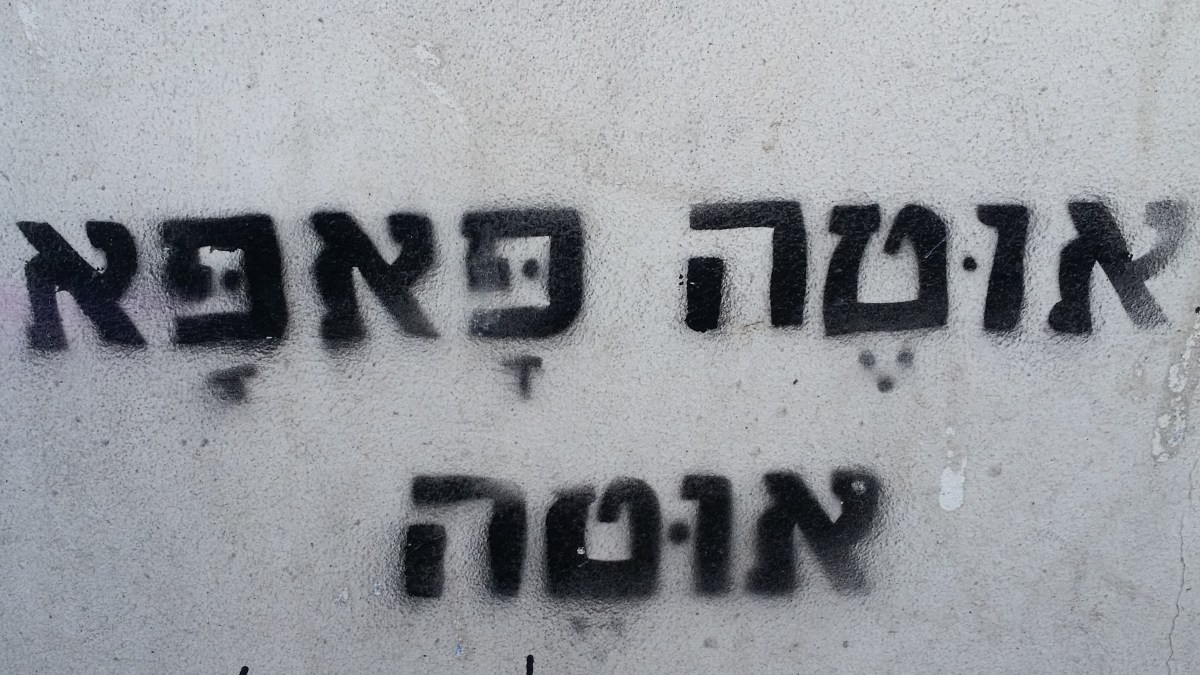

Last night, Yiddish came to life. At the beginning of the night, an Israeli came in and tried to take one of the three chairs at my tiny table. I said: “actually that chair is for Yiddish.” He said “well, nobody is going to come anyways, so I’ll take it.” I said: “nope, this chair belongs here, you can leave now.” I asked him if he wanted to learn something and he said “sure, teach me a word.” I did, he laughed, gave me one of those “everything is OK dude” Israeli high fives and left. Probably without a further thought about what he had said.

The best part of the evening is that this guy was totally wrong. Group after group came over to my table. We didn’t have enough chairs. When all was said and done, about 15-20 people had visited my table. A German guy and two Dutch men explained how Yiddish had made its way into their languages! A Brazilian Jew talked about Yiddish in her family. I met Israelis whose parents or grandparents spoke the language and remembered some phrases. Together, we read my copy of “Der Blat”, a Satmar Hasidic newspaper. And I could see the glow in their eyes when they realized they could understand some of it.

What was also astonishing was how willing people were to learn. I often find Israeli culture frustrating because of the bravado. So many people here feel the need to be right trumps all. Hence often endless debate, even when the facts used are minimal. I’ve even had Israelis try to correct my English- knowing I’m American. We often laugh that off, but after a while it wears on you. It’s tiring having to constantly defend yourself. Humility is not an Israeli value.

Yet at the Yiddish table, Israelis came to learn from me. And subsequently shared about themselves. Their families, their stories, their grandparents’ Yiddish phrases. For the first time, I actually felt in dialogue with Israeli Jews rather than a lecture. Or an argument. There was a softness to our conversation that made me happy. It warmed my heart and it gave me hope.

In a society where, as I see it, traumatized Jews faced 2,000 years of violent persecution with few options for safety and survival. Sadly, some of these Jews ended up traumatizing and displacing Palestinian Arabs in a bid for a homeland. Some of these traumatized Palestinians subsequently re-traumatized the Israelis. And now we’re stuck in a seemingly endless cycle of violence.

That’s how I see it on regel aches- or “one on leg” as we say in Yiddish. My Tweet-length version of the conflict here. The saddest part is the trauma on both sides continues. Anti-Semitism is not just the Holocaust. It’s a two-millennia phenomenon that continues to this day from America to France to Iran. I’ve personally experienced it in the liberal suburbs of Washington, D.C. When Jews are persecuted, we often have nowhere to go, which is why some people believe in a Jewish state. I’m not sure it’s the best solution and I completely understand why people feel we need it. It’s not by accident that there’s a lot of French people in Israel- they’re Jews fleeing violence and bigotry. Palestinian terrorist attacks on pizza shops and buses and schools only feed this narrative as we feel under attack yet again. Trauma piled upon trauma.

And for the Palestinians, you have those who are citizens of Israel yet continue to face discrimination, racism, and often poverty. Whose lands were robbed of them- and are still in the hands of the Israeli state 70 years later. You have those in the West Bank and Gaza Strip who live in immense poverty, have little right to travel, have few if any civil liberties, and often face violence from the Israeli military. And even some settlers who burn their trees, deface their houses of worship, and physically assault them. And you have Palestinian refugees in Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and elsewhere who can’t even come back to the land they once called home. Who have no rights in the villages they come from and whose host states often extensively discriminate against them.

Sometimes its enough to just make you cry and cry and weep for humanity. With no end in sight. Ya Allah, God please send us all healing.

So in the face of all this sadness, what gives me hope? Yiddish. Because tonight, I saw the softer side of Israeli Jews. When they don’t have to be “tough”- not against Arabs, not against other Jews, not against their own heritage. Rather, by connecting to their roots- roots violently uprooted both by European anti-Semites and the Israeli state– they felt warmth.

I hope politicians can figure out a solution to this problem. Given their proclivity for narcissism and greed, I’m not sure what they’ll do. In the meantime, perhaps part of the solution is culture. When you feel connected to something bigger- especially something a part of your heritage- it puts things in perspective. Rather than having to show how “Israeli” you are, you can be the multifaceted Jew beneath the uniform. The Jew whose family was persecuted by Polish Nazi collaborators, the Jew whose family escaped to Israel, the Jew who lives on Palestinian land, the Jew who wishes to reconnect with his heritage. A complex one, of persecution and co-existence. Of perseverance and of trauma.

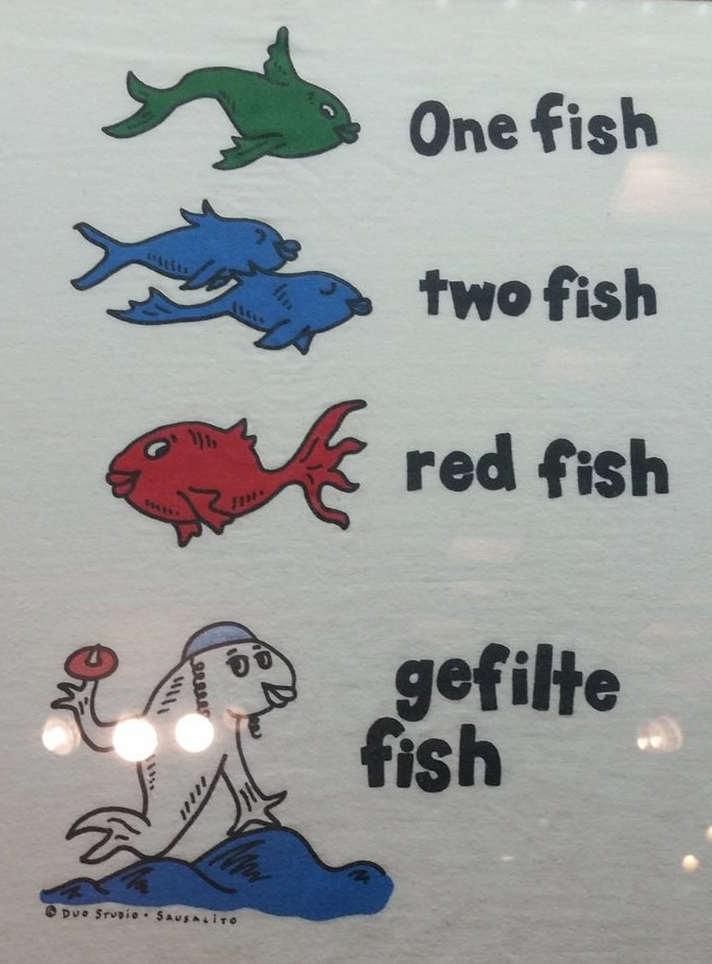

A little less prickly sabra and a little more soft kneydlach. Those fluffy yet durable matzah balls that comfort you when you feel sick.

—

Cover photo by Jonathunder – Own work, GFDL 1.2, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=31812266

You must be logged in to post a comment.