Lately, as some of you have noticed, I’ve felt rather down. Job hunting is stressful- and job hunting in Israel is even more so. Sending resume after resume, LinkedIn after LinkedIn, call after call. It’s exhausting. And knowing that the salaries here are so much lower than the U.S. doesn’t help. As I’ve written about, Israel is one of the most expensive countries in the world. Tel Aviv is the 9th most expensive city. Yet the salaries don’t keep pace. Out of the 34 OECD countries, Israel is ranked 23rd in purchasing power. According to Numbeo.com, an average meal at a low-cost restaurant is $14.78 in Tel Aviv and $20 in New York. New York rent is also more expensive, although Tel Aviv is actually more expensive than the Big Apple if you want to buy an apartment outside the city center.

In that spirit, let’s compare apples to apples. While most indices for New York are more expensive than Tel Aviv (although milk is 33% more expensive in Tel Aviv!), you have to remember the salary gap. The average net salary, after taxes, is $4,505.72 per month in New York and just $2,294.76 in Tel Aviv. And Tel Aviv is where most of the high paying jobs are in Israel.

All of which is to say that although New York is known for being one of the most expensive cities in the world, a place where most Americans couldn’t dream to live, Tel Aviv is actually worse off economically. The average Tel Avivi has 14.96% less purchasing power than a New Yorker.

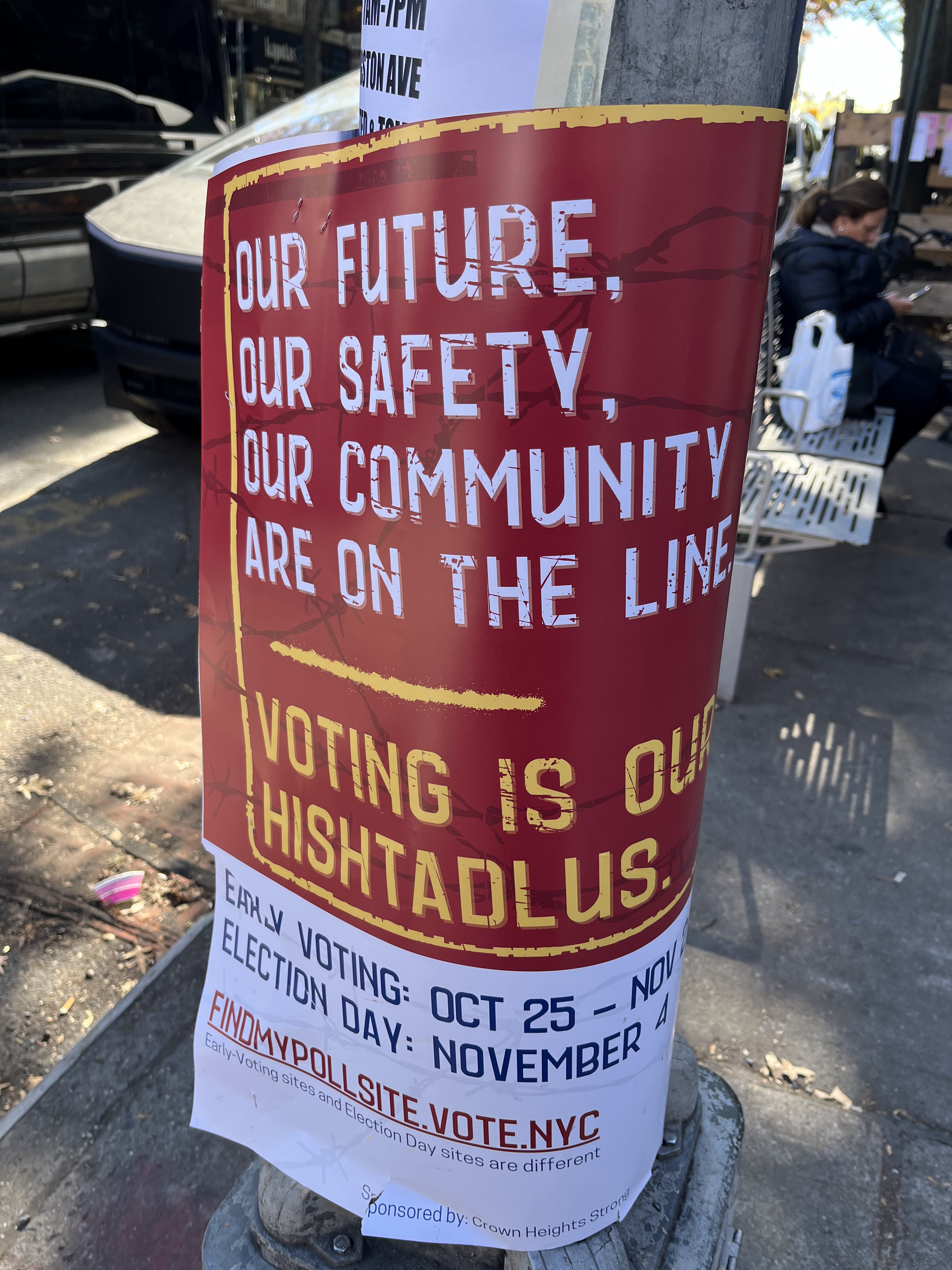

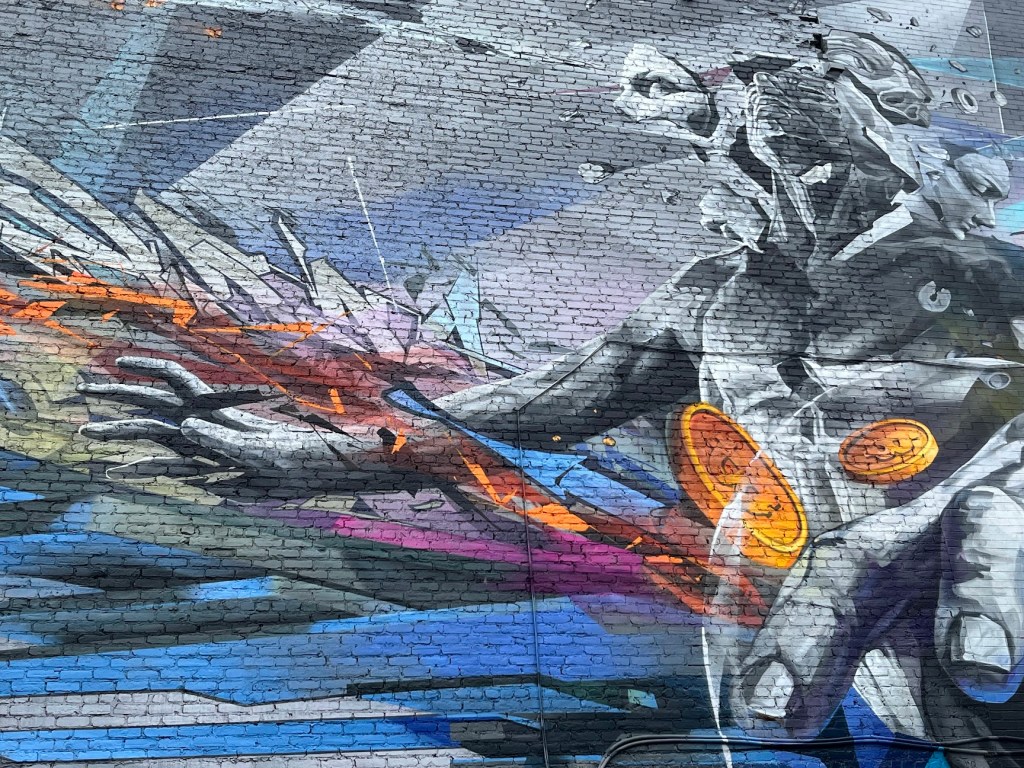

It’s an economic desperation you see on the streets here. Today alone I noticed two different grown men rummaging in trash bins in the middle of the city. Looking for food, I presume. A degrading experience for them, and a deeply sad and disturbing one for me to see. It makes me read signs like this one, which I saw at a bike store, with a bit of irony:

Of course, these problems are not only happening in Israel. Around the world, the gap between wealthy and poor has become a pressing issue. When I was in San Francisco last month, I saw more homeless people than possibly any other city I’ve visited. Rural Romania, where I spent some time hiking and backpacking, has largely been hollowed out by migration to London and Spain and Italy in search of work. Village economy has dried up after joining the EU.

The thing is not everyone is suffering here. In 2018, Israel counted over 30 billionaires. In dollars. High-tech firms here are some of the most successful in the world, with some of the highest salaries in Israel. If you work in the start-up scene, Israel is the place to be and you could probably build a comfortable life here if you choose to make aliyah.

On the other hand, with the cost of living continuing to increase and other industries’ salaries failing to keep pace, Israelis are being left behind. Including olim like me. Who came here with a Master’s degree from Georgetown university, 8 fluent languages (including Hebrew), and 10 years of public relations experience.

I have some more meetings in the next few days. I have been sending out my resume left and right, networking like a maniac. Those of you who know me personally know I am an extremely proactive person. Root for me, encourage me, I need it.

I want to share some stories from this journey.

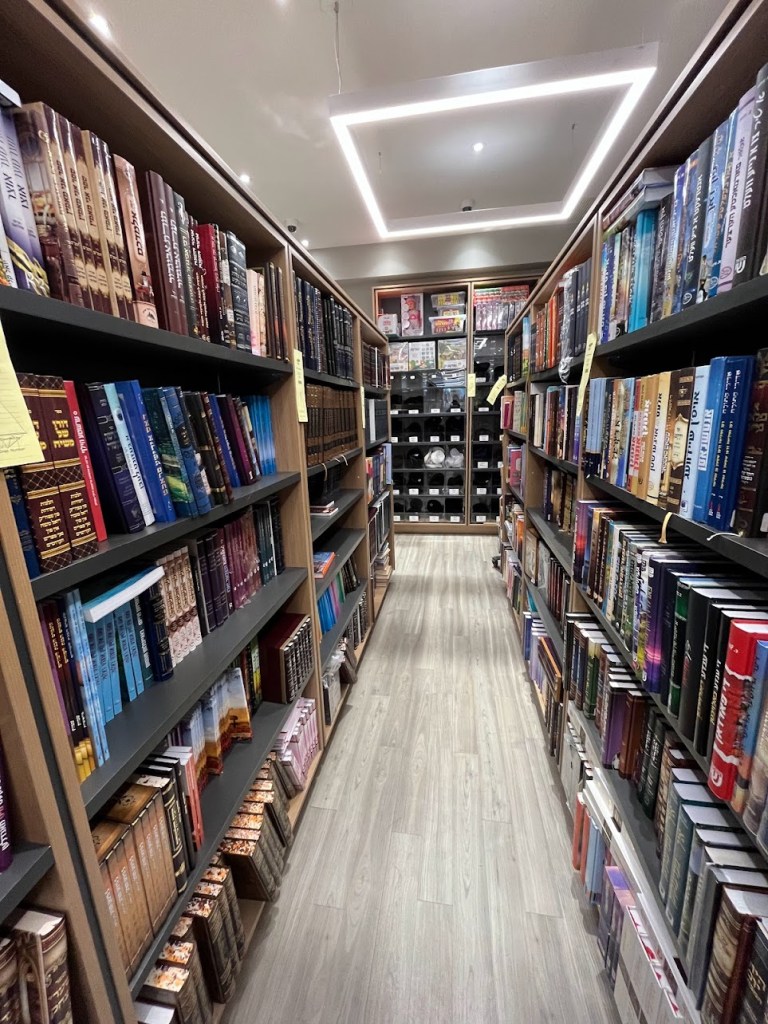

Last week, I went from bookstore to bookstore in Jerusalem. Calling, showing up in person, filling out forms. I figured it’d be good to earn some money while searching for a job with a real salary. No call backs. I was even told by one bookstore that I was “overqualified”, even after explaining I was just looking for part-time work. I also spoke to an employee of an Israeli travel company I was trying to network with. With the hopes of collaborating on my blog, to hopefully earn some revenue and bring them business. After I sent some English and Hebrew writing samples, the employee wrote to me: “it is hard to impressed by your writing.” It was like a gut punch. I know I’m a good writer- and the 50,000 people who read my blog are proof. As are the wonderful comments you all share with me. But it’s just demeaning. How long should I fight for an underpaid job here?

Needing a break from the stress of job hunting- a hunt which at this point is extending to both Israel and the U.S. out of necessity- I headed to a museum. Knowledge, history, learning- these things always light me up and give me hope. Seeing the long spectrum of Jewish history and the beauty of art helps put my current struggles into perspective. And fills the soul with light when people around you are swallowing your hope alive.

When I visited Italy last march, I learned about the unique history of Italian Jews. A 2,000 year old community, they predate both Sephardic and Ashkenazi Jews and have their own rite. At the Jewish Museum of Rome (which I highly recommend visiting), I learned there was another place in the world where the Italian rite was used: Israel.

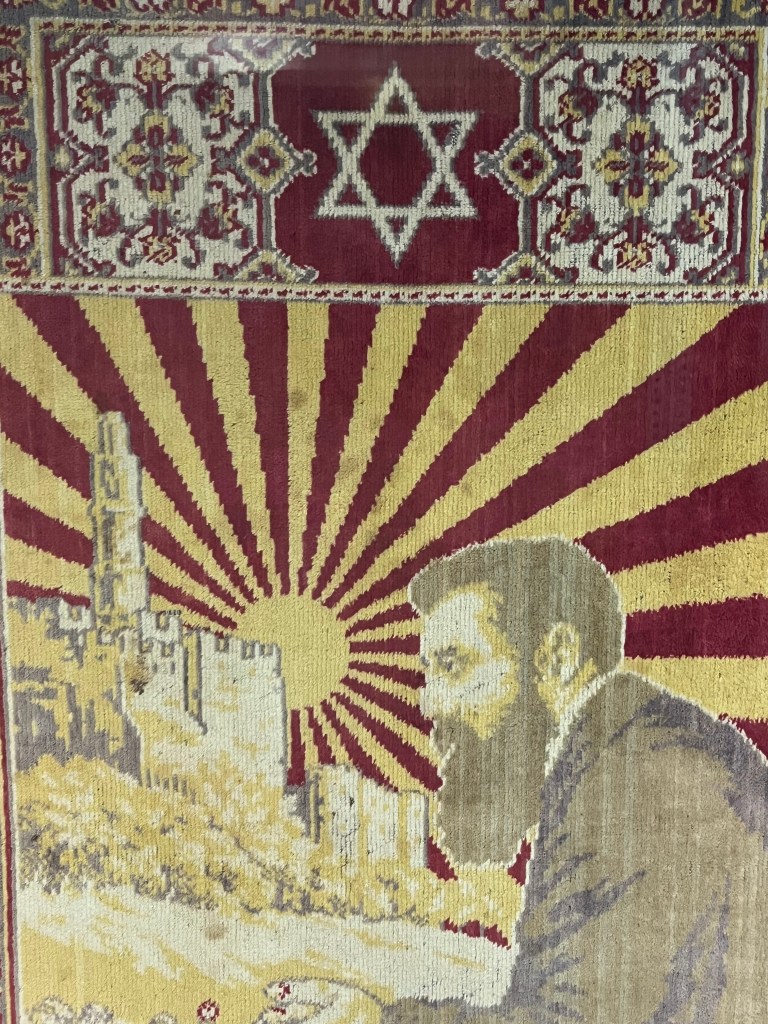

In one of the most miraculous stories I’ve ever heard, Italian Jews transported an entire historic synagogue to Israel in the 1950s. In a bid to preserve this ancient Jewish heritage- seen as endangered even after the Holocaust- the building made its way to Jerusalem where it is now housed in the U. Nahon Museum of Italian Jewish Art. It’s a small but absolutely stunning museum. With ancient and medieval Italian Jewish artifacts, and the synagogue itself. It is used to this day- and has extremely rare Italian-rite prayer books which I got to hold and read up close.

The museum is a testament to Jewish history and the power and nature of Israel itself. In the museum, I read from the Sereni Haggadah, a 15th century Italian book illustrated with Ashkenazi motifs and written according to their rites. I read about how some Italian Jews even spoke and published in Yiddish. A reminder of how all Jews are connected- that Ashkenazi, Sephardic, and Italian flow into one other. In the sun-soaked land of Italy, where all three communities have co-existed for centuries.

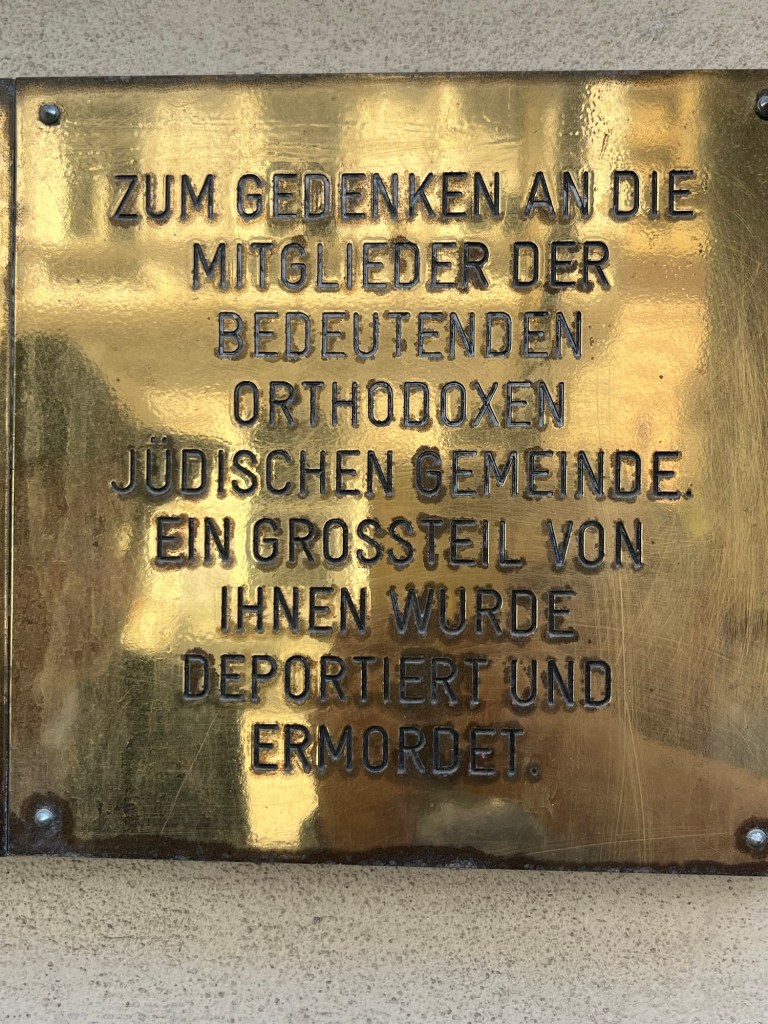

The synagogue and the museum are a reminder of the power of the Zionist ideal. Without Israel, who knows what would have happened to these treasures, to the synagogue itself. While some synagogues in Europe are preserved, the vast majority have been destroyed or lay in decay. I saw some turned into restaurants and casinos and there is even one that was turned into a strip club. But more than anything, they are usually locked and empty. To prevent continuing theft and anti-Semitic attacks, an eerie testament to their largely emptied communities.

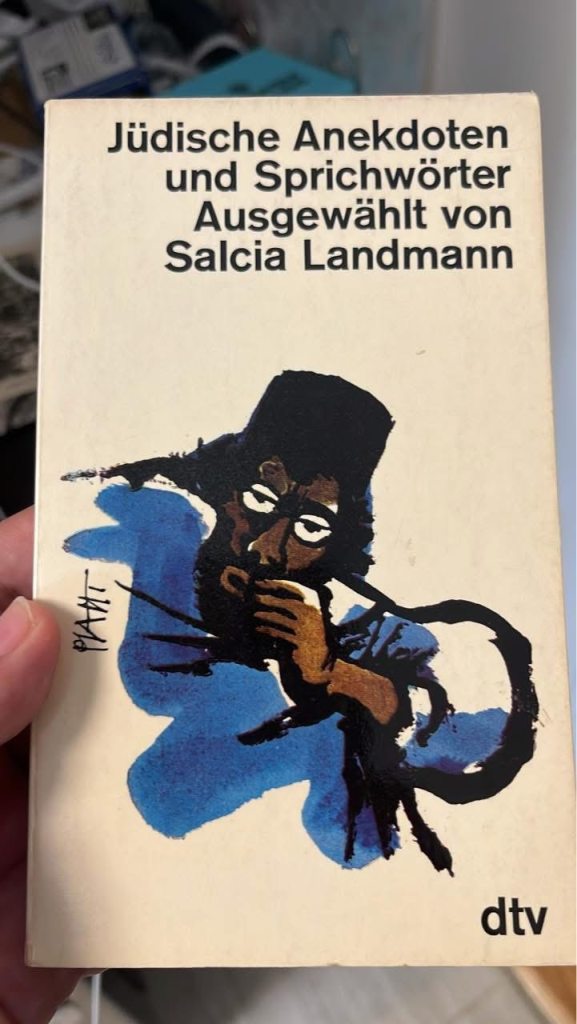

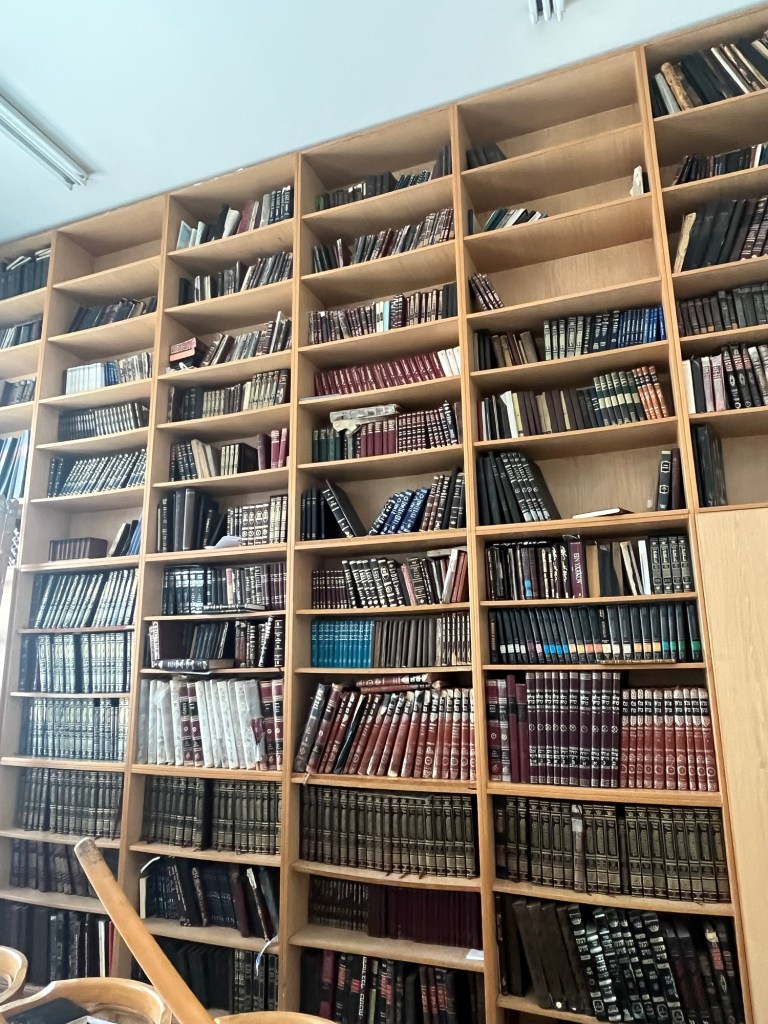

Israel was the logical place to send this synagogue. It’s a place where the history of the Jewish people can sit safely, far out of the reach of anti-Semites. It’s a place where the National Library of Israel preserves 5 million Jewish books, audio files, and other treasures. An unmatched collection spanning continents and centuries. A gold mine I got to explore this past week. The only library of its kind. I perused Judeo-Arabic versions of the Torah, Catalan-language books about Jewish history, dialect maps of Yiddish, and a book about the xuetes of Mallorca, Jews forced to convert to Christianity. Who manage to maintain a separate, often persecuted, identity to this day. Check out the library’s website and discover a digital collection that can transport you from your home to almost any Jewish community- past or present. If you’re in Jerusalem, go visit! There are real gems right under your nose- and it’s free!

While visiting the Italian museum, I met some foreigners, who were intrigued by the exhibit. Including Jews. I spoke with a British Jew whose parents are Israeli. He only speaks a few words of Hebrew, but he connects to his Judaism by studying Italian Jewry. The museum staffer himself had Mexican parents and we spoke in Spanish about the siddurim.

I also made a point of talking to several sabras, or native-born Israeli Jews. This segment of the population tends to have the least appreciation of Jewish heritage. Israeli schools teach a lot of biblical history and a lot about modern Zionism. But Diaspora communities of 2,000+ years are often relegated to discussions about the Holocaust. Undoubtedly a painful watershed event for world Jewry that a third of Europeans don’t know about. But hardly the only thing worth mentioning in two millennia of history. Marked by both persecutions and amazing perseverance and creation. It leaves the average sabra deeply ignorant of Jewish communities outside of Israel, something I see reflected in the growing gap between American and Israeli Jewry. Clearly a gap that has origins on both continents, but which I see little effort to tend to here in Israel.

More than this, it also leaves Israelis ignorant of where they come from. Here our history dots the landscape. Ancient Jewish archaeological sites sit in every corner of the country. Ritual baths, or mikvahs, built two thousand years ago- the kind I have personally used at my synagogue in Washington, D.C. I have even done a genetic test- and my DNA is closest to Syrians, Lebanese, Greeks, Sicilians, and Palestinians. Our guttural Semitic language was birthed in this land. Yet we also were enriched- at times oppressed- by the cultures we have engaged with since our expulsion from here. And without understanding the intermediate 2,000 years, the average sabra doesn’t really know a lot about how he or she came to be. And what it means for the Jewish people- or our state- today.

Two sabra women I met had Iraqi parents. I think being the children of olim, especially ones so ruthlessly expelled from Iraq, made them more open to learning about Diaspora history. Perhaps just as importantly, they knew about their own rich heritage, so it might have made them more appreciative of other Jewish cultures. I sensed their awe as they looked at the synagogue, admired its beauty, and stood in wonder at its journey from Italy to the capital of the State of Israel. A journey Italian Jewish slaves in Rome 2,000 years ago never could have imagined. Yet worked and prayed for- and whose descendants made a reality.

There was one young sabra in the museum, otherwise the latest generation was nowhere to be seen. It’s a stark reminder that once you are cut off from your roots, and as you grow new ones, it is hard to inspire people to reconnect. It’s a phenomenon I struggled with almost a year ago to the day. My journey to learning Yiddish as an adult proves that reconnecting with the breadth of Jewish history is possible. And some young Israelis, like the phenomenal Yemenite singers of A-WA, are joining me on that journey. As they go around the world singing traditional Judeo-Arabic songs to sold-out clubs. I personally have seen them three times on two continents- go experience the magic of Yemenite song! They are keeping their chain of tradition alive while innovating along the way. A fitting testament to two millennia of Yemenite Jewish heritage and to the fact that it has survived at all. Thanks to Israel, where almost all Yemenite Jews live today after being expelled in the 1950s.

There is a certain push and pull, perhaps even an intertwined irony to having a Jewish state. The state has saved the lives of hundreds of thousands, maybe even millions of Jews. Jews whose countries senselessly butchered them or confiscated their property and expelled them. From the U.S.S.R. to Morocco, from Algeria to Poland, from Germany to Iraq. While some Jews have come here voluntarily, the vast majority have come under major duress. I couldn’t help but notice an Italian and Hebrew prayer in the museum this week dedicated to saving Alfred Dreyfus. The French Jewish army captain ruthlessly persecuted by his countrymen, by anti-Semites just over a hundred years ago. Reading that prayer in a museum in Israel reminded me of the importance of having the ability to protect ourself. That while we work with allies wherever we can find them, we have just as much a right to defend our people as anyone else. Which is why we have put our lives on the line to make sure the State of Israel exists for all of us.

At the same time, it’s clear that nationl-building has come at a price. As it does in all states. Where minority cultures, where immigrant cultures, where the “other” is often ruthlessly assimilated until it is almost unrecognizable. To this day, France won’t sign a European treaty recognizing its minority languages. Arab governments such as Morocco and Algeria have forcibly assimilated their native Berber populations linguistically and ethnically. A deep marginalization that continues to this day. Turkey for years claimed that Kurds were simply “mountain Turks” despite their completely different languages.

For Jews, the curious thing is we did it to ourselves. While for sure in Diaspora communities, Russians, Americans, French, and others have pushed us to assimilate into their cultures, in Israel, Jews did it to other Jews. In other words, the sabras already living in Israel identified as the “new” Jews- strong, masculine, assertive. And the old “effeminate” and “bookish” Jews of the Diaspora arriving here had to be reformed. Which is why ancient Jewish languages like Yiddish and Iraqi Judeo-Arabic and Ladino were basically thrown out the window. Hollowed out. Jews were forced to take on a new, uniform Israeli identity. To be more sabra and less Shmuly. In some sense, more Israeli and less Jewish. At least as how Judaism had been conceived of until then. An odd statement to digest.

Some of this is the price you pay for building a nation. Without a certain degree of cohesion, could Israel have successfully resisted Arab invasion after Arab invasion? Could a Yiddish-speaking commander have successfully (and quickly) communicated with a Moroccan Jew who spoke Arabic? If Israelis had had the luxury of being the Switzerland of the Middle East (not coincidentally, a country with four official languages), maybe it would have been seen as more feasible. To allow a bit more room for diversity. But our nation was not given an easy start. So practicality took precedence over preservation, and entire Jewish civilizations were wiped out or cannibalized. A couple weeks ago, I entered a Persian restaurant in Jerusalem (Baba Joon by the Centra Bus Station- the best Persian food I have ever eaten) and the really friendly waiter was clearly proud of his heritage. But he didn’t know how to say “you’re welcome” in the language his ancestors spoke for 2,500 years. I taught him, which made him smile. There are people who want to connect to their heritage here, but it is hard and there are those who resist. Partially to avoid painful memories of persecution, but partially because they’ve been taught that that “Diaspora stuff” is worthless. It’s the dustbin of history.

But that’s wrong. To wander is to be Jewish. Whether physically, as in the case of Jews across the centuries. Or intellectually, by visiting the National Library, by learning your ancestors’ language, by going on an unexpected hike or to a new museum. To explore, to devour knowledge, to take the untrod path- that is Judaism. We’ve been wandering since Abraham and our legendary trek in the desert. On our way to the Promised Land. Just because we have a state now doesn’t mean we should stop our inquiry, our curiosity, our search for the unexpected connections that bind us together and enlighten our selves.

At the end of the day, I stood in line at the grocery store. Feeling disillusioned, stressed, in need of a smile, I struck up a conversation with the friendly Russian Jewish clerk. In Slavic-accented Hebrew, she asked me how I was doing and what I was up to. Our conversation roamed. We talked about aliyah, the struggles. She told me how she was Russian but her parents were Polish. And how she only thought there was sweet gefilte fish until she moved to Israel, unexposed to the salty southern varieties of Ukraine. A country that in her own words, she inexplicably detests. Israelis are full of contradictions like all people, but we have a bit more courage to say them out loud.

We laughed as I told her my great-grandparents used to make this food by hand. Putting entire carp in their bathtub and making the delightful fish balls one by one.

She then asked the best question. “Redstu yiddish?” Do you speak Yiddish?

And I said “yo! Ikh ken Yiddish!” I do speak Yiddish!

And right there, in the line at the grocery store, as an impatient sabra waited behind us, we chatted in mamaloshn, the mother tongue. A tongue our ancestors have shared for generations. Filled with warmth and love and the smell of rich chicken broth bathing kneydlakh in the Passover kitchen. Not to mention a literary tradition that has produced thousands upon thousands of books filled with wisdom, now available for free digitally at the Yiddish Book Center.

In the end, my Yiddish and my Hebrew co-exist, if at times uneasily. I am no less fluent in one because I speak the other. In fact, one helps me understand the other, as the languages overlap and have enriched each other throughout Jewish history.

It’s a symbiosis I hope sabras can achieve. That while building a state does require new models and sacrifice and adaptation, it doesn’t have to completely erase our rich and complicated Jewish past. To relegate it to nothing but our Shabbat foods, to museums, to archives.

Judaism is alive and kicking. Despite all the people and peoples who have stood in our way.

The question we face now is what kind of Judaism? Having built the first Jewish state in 2,000 years, one that continues to require our vigilance to protect, perhaps we need to shift our focus.

Our focus was once state building. But now the question is what kind of state we want to live in, or have as a safe haven?

Do we want a state where a few people earn millions of shekels in high tech while middle aged men scrounge for food in trash bins? A state where Jews live disconnected from their own rich heritage, on whose very land Jews mostly spoke Yiddish and Ladino until the 1920s?

Or do we want a state where people can earn a living. Where, if not rich, people can survive, can build a career. Can contribute to our people and our economy and connect with the world no matter how wealthy they are. Where the Russian grocery store clerks who have PhD’s in chemistry can practice the profession of their training. Instead of giving preference to sabras, who are in some cases far less qualified.

Do we want a state where you can be both Israeli and Moroccan, the kind of hyphenated, hybrid identities that hold so much potential. That have enriched Jewish history for millennia. That might even enhance empathy and understanding among Jews of all backgrounds. And now offer us the rare opportunity to fuse our past to present, without erasing where we’ve been.

My answer is I hope so. I won’t say yes because most things are out of my control and if there’s one thing I’ve learned from Jewish history and from living in Israel, it’s that things are complicated.

But I believe, at the end of the day, that it’s better to strive for something better than to sit stationary, stewing in malaise.

I don’t know where my journey will take me. I don’t control the Israeli economy, but I do care about contributing to its society. And I will do so wherever I find myself, even if for economic reasons I find myself longing for a warm plate of jachnoon from the other side of the Atlantic.

One day, I hope to sit in the Museum of Italian Art in Jerusalem. To guide tours for hundreds of bright young Israelis eager to learn about their heritage. To connect them with Jews and non-Jews visiting the same museum from around the world, who value them as Jews and as human beings. Who see their past and their present as intertwined with their own and worthy of their care.

I hope to sit in that museum with a budget. A budget the government will dedicate not just to security, not just to elaborate national ceremonies, not just to the hundreds of rabbis it employs.

But also to our culture. To our institutions. To the humanities, to our humanity that has persisted over generations. To educators, to social workers, to artists, to after-school programs, to scholars, and to social innovators. Not just social media.

So that one day, a well-educated, passionately-Jewish oleh like me can find a well-paid job. Preserving our heritage, educating for tomorrow, and not just running pay-per-click campaigns from the 9th most expensive city on the planet.

Im tirtzu, if you believe it, it is not a dream. This is the next frontier. May we be the pioneers.

—

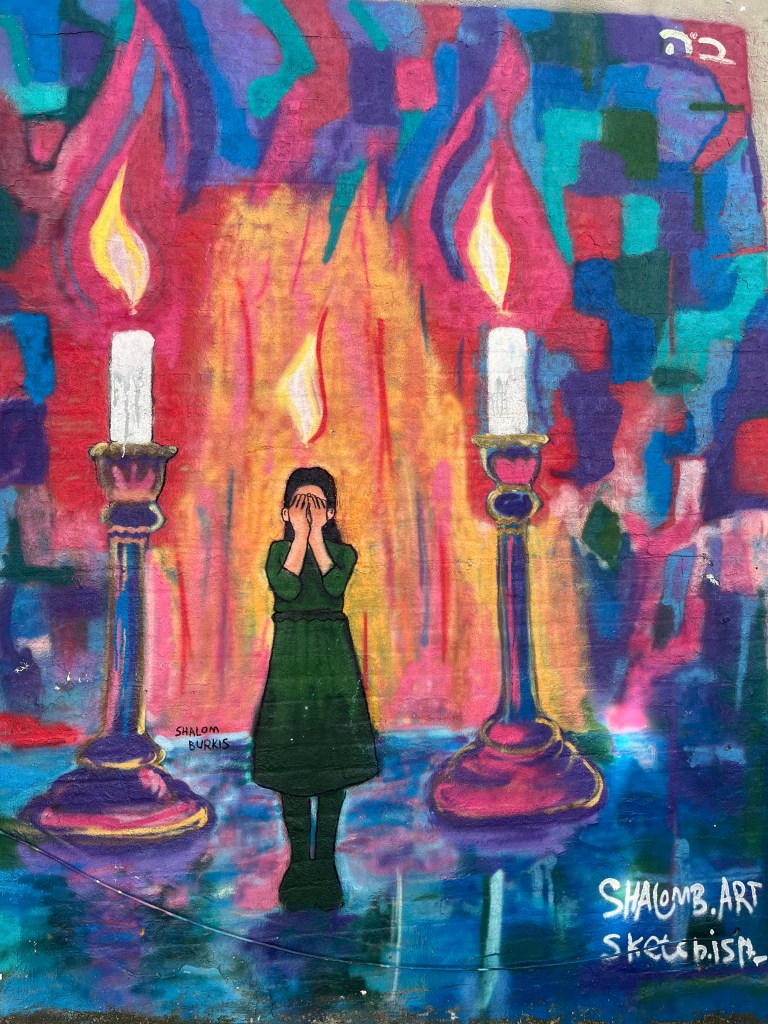

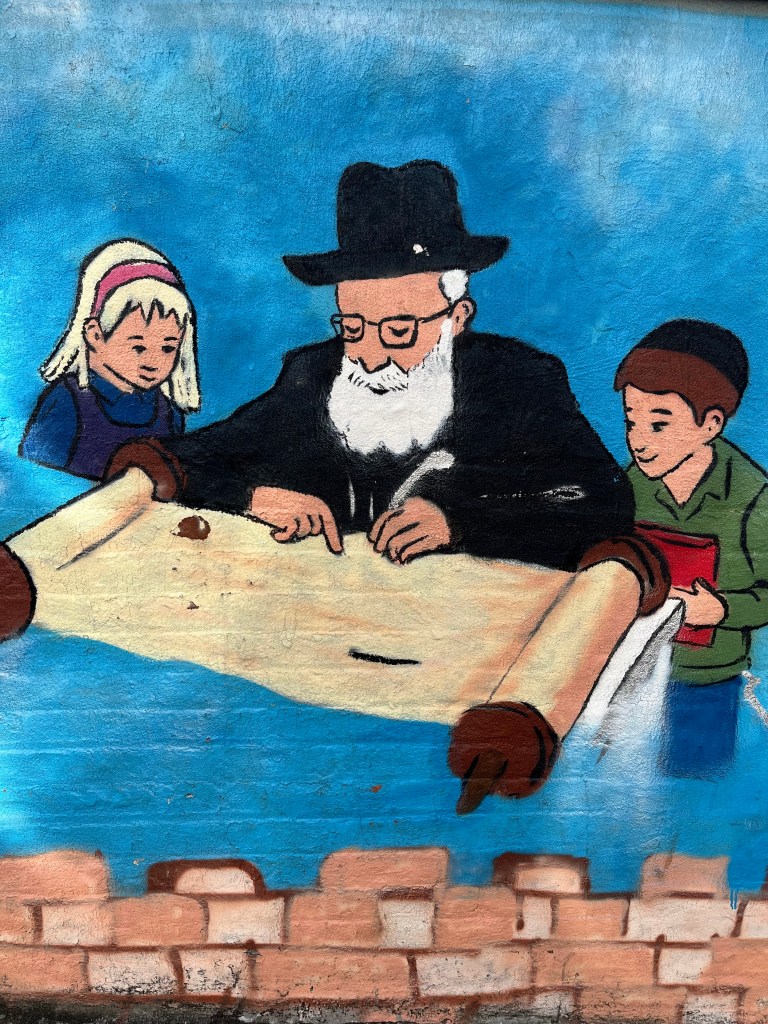

My cover photo is a medieval Italian Jewish painting. Proof that our creativity extends not only to high tech, but also to high art.

You must be logged in to post a comment.